By Lisa Shelton

Evolution of Long-term Care Design

For a long time, the medical model drove the design and planning of long-term personal care homes. Double-loaded corridors and nursing stations produced an institutional atmosphere, devoid of warmth and often dignity that aid in seniors’ health and well-being.

Over the last few decades, that has changed significantly due to insight and advocacy. Studies illustrating the built environment’s impact on seniors’ health and well-being, alongside growing public expectations concerning the quality of care afforded to seniors, have transformed the design intent of these places. We are more equipped to plan and design healthy environments for seniors to thrive in because of the abundance of multidisciplinary research at our fingertips.

Our firm has taken a visionary approach to improving environments for seniors since the early 1990s. In 1994, Rudy Friesen (ft3 founder and architect), with support from Fisher Branch Personal Care Home in Manitoba, implemented the Chez Nous philosophy of care to deinstitutionalize long-term care homes for seniors. Chez Nous translates to "Being at One’s Home" and describes a community of cottage-like homes in a clustered layout.

Senior staff at the Foyer Notre Dame in Notre Dame de Lourde created Chez Nous after touring Bethania Personal Care Home. In 1981, ft3 designed the expansion of Bethania without corridors at the client’s request, inspiring the Foyer Notre Dame staff to rethink the layout and configuration of seniors housing.

Home is an overarching theme when planning and designing homes for vulnerable groups. The successful realization of long-term care is no different. A Sense of Home often guides the form and function of long-term personal care homes. At the same time, it’s vital to remember that these homes are Still Healthcare environments, requiring specific healthcare design standards and infection protection controls.

So, how do we find The Right Balance between capturing a homelike sensibility and maintaining critical healthcare design standards and infection and protection controls?

Let’s explore.

A Sense of Home

Home is a term we’re all familiar with even though it looks different for each of us. Is home a place? A feeling? Or both? Home is often where we feel most comfortable because we can shape the environment to suit our needs and personality. It’s where we keep the trappings of our lives, illustrating and communicating what we find meaningful. Home provides the basic human need for control and privacy.

Therefore, creating a Sense of Home within long-term personal care home environments is intrinsic to the well-being of residents. As interior designers, our challenge becomes evoking the look and feel of a home to multiple residents with complex, diverse, and changing needs. Not to mention, different ideas of Home.

A natural evolution of Chez Nous and the Eden Alternative is the Small House model. The Small House model champions freedom of choice and autonomy within long-term personal care homes by grouping seniors in smaller households (10 to 12 residents), enabling them to replicate familiar domestic routines and participate in the larger community while strengthening the relationship between residents and staff.

The Small House model informed the redesign of Boyne Lodge Personal Care Home in Carman, MB, to improve the campus’ facilities and create new space for 80 additional residents. The design organizes seniors into smaller homes of approximately 10 to 12 residents, who are often grouped by shared or similar personalities, needs and interests.

"While the overall design of each household in Boyne Lodge is the same, the intent leaves aesthetic breathing room for customization that appeals to and reflects its residents."

In long-term personal care homes designed from an institutional perspective, seniors often shared rooms, and privacy remained a luxury. Boyne Lodge integrates a private bedroom and bathroom (including a shower) for each resident, providing privacy and security while underscoring their Sense of Home by allowing personal space for familiar and meaningful possessions.

A mixture of appropriate amenities and thoughtful aesthetics within the household’s spaces heavily influence seniors’ physical, cognitive, and emotional capabilities. Jan Golembiewski, who has a PhD in psychological aspects of architecture, and John Ziesel, an expert on dementia care and treatment, explain that differentiating common spaces helps residents behave socially and appropriately. When designers plan spaces with the appropriate character, messages, scale, furniture, and features, it promotes Behaviour Settings, helping define and communicate the intended use of the space to residents.

Meanwhile, everyday aesthetic preferences and decisions — even seemingly insignificant ones such as the texture of bed sheets, meal place settings, and shower curtains — have a more powerful impact on forming an identity and perception of the world than high art.

While the overall design of each household in Boyne Lodge is the same, the intent leaves aesthetic breathing room for customization that appeals to and reflects its residents. Shelving, tables, and seating provide the household flexibility for adapting the space to their interests or needs, such as playing the piano or working on puzzles and crafts.

The Small House model takes a decentralized approach to dining. Residents can adhere to their routines instead of conforming to the facility’s schedule, as meals happen in each household rather than in a large dining room hosting the whole facility. Moreover, full kitchens within each household allow residents to participate in meal rituals such as setting the table or overseeing meal preparations.

As an age-in-place campus, Boyne Lodge features community amenities, such as the family resource centre and bistro, that service Boyne Lodge and the larger community, enabling residents to have real and tangible connections to people outside the facility.

When siting the new building on the Boyne Lodge campus, the goal was to ensure it was successfully immersed within the surrounding community to cultivate a Sense of Place. With Boyne Lodge nestled along the community walking path following the Boyne River, balconies and patios lean into the river path. The sentiment is that families walking past Boyne Lodge will feel like they’re walking past grandma’s house.

Still Healthcare

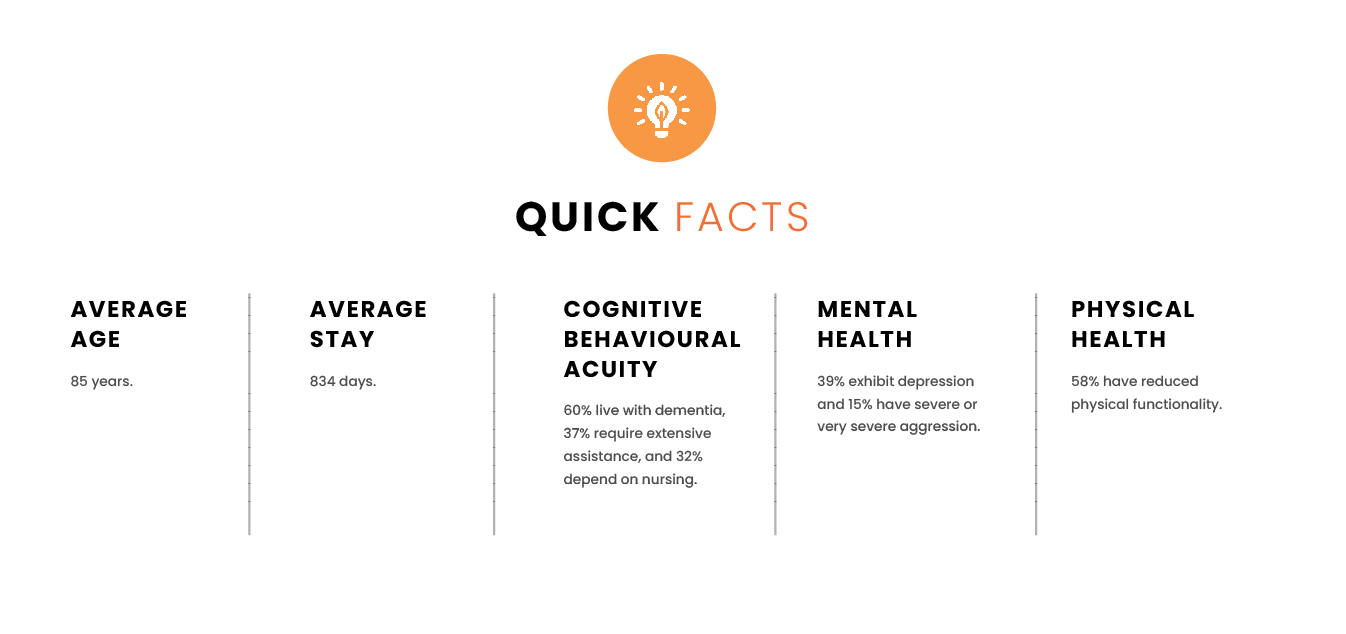

On average, seniors entering long-term care homes are 85 years old and stay for approximately 834 days. Many residents also live with dementia or another neurological disease, experience lower physical functionality, and require extensive assistance and nursing care to complete daily living activities.

This project type falls into a Group B Division 3 occupancy classification of the National Building Code. This classification means it’s a group care environment and demands more rigorous building requirements for life safety.

When one overlays this with capital and operating budgets, Infection Protection & Control (IP&C), and facility maintenance requirements, the interior design toolbox required to meet government and health standards for this project type contains fixtures, furniture, and finishes that tip the scale to the institutional side.

Typical design tools that help interior designers capture and communicate a theme or an emotion don’t operate in the same fashion as other environments.

For example, soft light-filtering drapery that gently moves with the breeze of an open window creates natural movement patterns resembling tall grasses, aquarium fish, and light or shade patterns created by cumulus clouds. While these naturally occurring, non-rhythmic stimuli capture attention and create positive interventions compared to regular mechanical movement, which can evoke neutral or negative emotions over time, they also can pick up dirt and pathogens that can negatively impact residents’ health.

While décor items aid in creating a residential-style atmosphere, factors related to dementia, additional cleaning, and potential hazards for residents limit this intervention. Therefore, interior designers must find creative ways to tip the scales back to the residential side.

"While décor items aid in creating a residential-style atmosphere, factors related to dementia, additional cleaning, and potential hazards for residents limit this intervention."

In 1979, Aaron Antonovsky, a professor of medical sociology, coined the term Salutogenesis to describe the study of the origins of health, including factors sustaining human health and well-being, rather than the factors causing disease. Salutogenic research, including in dementia care environments, focuses on supporting a person’s internal adaptive capacity in three main areas: physical (manageability), intellectual (comprehensibility), and affective (meaningfulness). The composite of these elements forms an individual’s sense of coherence, and their sense of coherence is a powerful predictor of psychological health, even with the challenges associated with aging and dementia.

Our internal resources erode as we age, and our environmental sensitivity intensifies, negatively impacting seniors’ ability to understand and navigate spaces.

Many seniors experience spatial memory deficits, especially those living with dementia, and designing spaces that avoid causing residents additional distress is pivotal to avoid depleting their internal resources. Destinations located around corners or down a long hallway with no identifying landmarks or multi-modal cues allow opportunities for seniors to fail instead of succeed while participating in life’s daily activities.

Other fundamental design considerations extend to light levels, surface glare, and poor acoustic quality that can disable rather than enable senior residents. The freedom to move about purposefully and at will is meaningful, and meaningfulness is the powerhouse of our internal adaptive capacity.

The Small House model can help designers bridge the competing interests, goals, and limitations between beautiful design and healthcare design standards. Not only is the provision of private resident rooms in the Small House model beneficial for residents’ privacy and sense of home, but it’s also critical in controlling and preventing the spread of infections by containing illness and future outbreaks within resident rooms or households.

The Right Balance

Understanding our environment underpins our well-being. We experience our environment through our senses, and the greater the coherence among sensory inputs, the greater our understanding of our environment.

When we age and experience illness, our sensory perception and cognition weaken unevenly, reducing our ability to comprehend the world around us.

Colours, sounds, aromas, and textures reinforce what seniors see, hear, smell, and touch. A thoughtful spatial arrangement, using hierarchy and composition, can introduce order into the environment when there is complexity. This supports seniors’ sensory engagement and improves their comprehension.

Amplifying sensory engagement while maintaining healthcare design standards and infection control can be challenging but not impossible to execute. Tools such as colour, nature, and connections in our designer toolkit can reconcile these competing priorities to define spaces for seniors.

Colour

Our eyes can struggle to distinguish between colours as we age. Pale, cool tones, like blue and green, can be challenging for seniors to decode because of the eye lens’ yellowing or clouding. Warm colours like orange, red and yellow are easier to see for aging eyes.

Using saturated colours in wayfinding and value-contrasting colours to signal openings work well in long-term personal care spaces. With Boyne Lodge, value contrasting created a neutral, timeless backdrop within the households, extending the investment of the interior over time. It also allows staff and residents more opportunities to customize their household aesthetics.

Nature

Numerous scientific studies have discovered that direct or indirect experiences with nature in the built environment help reduce chronic pain, improve memory, lower blood pressure, help speed up patient healing times, and reduce mental illnesses.

Designing with nature is often referred to as Biophilic Design, and the principles it outlines (and varies depending on the source) include:

Biophilic interventions should never occur without intention or in a piecemeal fashion. Elements should complement and accentuate one another, creating an ecological environment that results in a wide spectrum of physical, mental and behavioural benefits.

While there are obvious ways of incorporating nature into interior environments (views of natural settings), it’s also possible to design interior environments with the qualities and features of nature that form more supportive and evocative ambient spaces.

The design of Rest Haven Personal Care Home’s atrium reinforces the relationship between the exterior and interior environments. The design team developed the atrium’s floor plan similar to an exterior landscape, creating pathways through the flooring treatment and raised planters delineating walking routes for residents.

"Rest Haven Personal Care Home’s atrium reinforces the relationship between the exterior and interior environments."

Perhaps the most stunning visual of nature within the atrium is the interior walkway inspired by a river or creek’s natural shape and form. It winds through the atrium like a gentle stream, supported by the surrounding clerestory windows and panes of natural wood and soft shades of pink, yellow, blue and green.

Connections

Wayfinding, sense of place, and interpersonal relationships are indispensable connections that support comprehensibility for residents in long-term care.

Deploying appropriate wayfinding elements is a crucial design strategy when defining connections between different spaces in the home.

Urban planner and author Kevin Lynch’s Five Elements of City Wayfinding can also apply to seniors housing, helping residents understand where they are and where they are going, especially when moving about outside the household.

Colour, artwork, images and patterns are great tools for developing multi-modal cues. However, correctly applying these cues is pivotal to their success. Contrast through different colours or alternating light and dark hues provide depth perception and delineation of features. Large-scale artwork, images, and patterns act as reference points. It’s important to note that implementing large-scale patterns compared to small patterns is pivotal, as smaller patterns can start vibrating or make seniors feel dizzy and confused.

The resident’s connection to the local context stems from the home’s textured materials, warm finishes, and comfortable furniture. The selection of the furniture and finishes invite people in, encouraging a meaningful connection to the surrounding context and culture of Carman, Manitoba, while evoking a relaxed and casual atmosphere.

In the Great Room, biophilic treatments appear in the tile around the fireplace, resembling the river rock found in the Boyne River. The wood-like finishes evoke the forests surrounding the facility with large floor-to-ceiling windows in the living room that immerse residents in nature while providing access to natural light.

On average, seniors live in long-term personal care homes for almost three years. Facilitating moments of social connection between residents, staff, and the greater community is essential for emotional well-being. While some residents prefer a more solitary lifestyle, it’s still important to design environments where these individuals can remain a part of the greater household and not isolated.

Interior designers can ensure human connection by interspersing long-term personal care homes with opportunities and cues that communicate spaces for socialization or create spontaneous moments of connection between residents, staff, and community.

At Boyne Lodge, the Great Room hosts events for larger groups and families while the households’ kitchen spaces encourage interaction by allowing space for daily living activities such as making food, playing games, and tidying up after meals.

Want to learn more?

The evolution of long-term personal care homes reflects a profound understanding of the relationship between design, health, and human experience.

As we strive to create environments embodying a Sense of Home, it’s essential to balance the residents’ emotional and aesthetic needs with the rigorous healthcare standards that govern these spaces.

Integrating innovative concepts like the Small House model that promotes autonomy and community within a nurturing environment and elevating residents’ ability to comprehend the spaces where they live and navigate, demonstrates how thoughtful design can significantly enhance the quality of life for seniors.

You can download a physical copy of this white paper by clicking here. If you'd like to learn more about designing and planning long-term care homes for seniors, please email info@ft3.ca to connect with our Health & Wellness team.